From Our Archives

Dan Clendenin, A Question From Dietrich Bonhoeffer (2011); and Debie Thomas, The Beloved Community (2020).

For Sunday September 10, 2023

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 12:1–14 or Ezekiel 33:7–11

Psalm 149 or Psalm 119:33–40

Romans 13:8–14

Matthew 18:15–20

This Week's Essay

A few weeks ago my wife and I attended a banquet to honor our former priest who was retiring after twenty-six years in the same church. On his last Sunday, he joked that he had really only preached one sermon all those many years, and that he saw no reason to change anything for his final homily. "It's all about love," said Father Matt.

There are good reasons for that condensation of the gospel into a single sentence. According to Jewish rabbinic tradition, there are 613 commandments in the Torah. You would go crazy, or become terribly sanctimonious, if you tried to obey all those many mitzvots. But Jesus, Paul, James and John simplify things for us; they all say that when we love our neighbor, we fulfill the entire law.

In Romans 13 for this week, Paul compares love to a debt that we can never fully repay. It's one of six texts that link our claim to love God with evidence that we love our neighbor. You can't have the former, no matter what you say or do, without the latter. No rationalization or excuse lets us off the hook. And to state the obvious, you can't love your neighbor if you don't even know your neighbor.

|

|

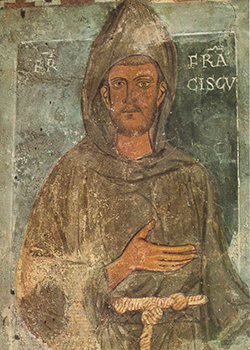

Oldest surviving depiction of St. Francis, c. 1229.

|

Paul writes: "Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for he who loves his neighbor has fulfilled the law." The entire Old Testament law, says Paul, all 613 of those commandments, "may be summed up in this one rule: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.'"

Writing to the Galatians, he said, "The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself in love. The entire law is summed up in a single command: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.'"

James 2:8 repeats this message almost verbatim: "If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, 'Love your neighbor as yourself,' you are doing right."

And then there's John: "If anyone says, 'I love God,' yet hates his brother, he is a liar. For anyone who does not love his brother, whom he has seen, cannot love God, whom he has not seen. And he has given us this command: Whoever loves God must also love his brother." (1 John 4:20–21).

Loving your neighbor, Jesus said, is the greatest commandment. In his last words to his disciples, Jesus called this a new commandment. "Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. All people will know that you are my disciples if you love one another." God's redemption of the world is mediated through the love of his people.

|

|

St. Francis renounces his earthly father, c. 1437-1444.

|

It's not obvious in what sense Jesus's commandment is "new." It's an ancient commandment that goes back 3000 years to the founding of the Hebrew community: "Love your neighbor as yourself," says Leviticus 19:18. Perhaps it's new to the extent that Jesus demonstrated the breadth and depth of God's love to every person he met, especially to his wayward disciples.

Love, said Paul in 1 Corinthians 13, is the greatest gift; without it I'm just a noisy nuisance.

Just as this ancient commandment was repeated throughout the New Testament, it was repeated in the centuries after the first believers. "Our care for the derelict and our active love," writes the African Tertullian, "have become our distinctive sign… See, they say, how they love one another and how ready they are to die for each other."

"Blessed is the one who can love all people equally," said Maximos the Confessor, "always thinking good of everyone."

In his commentary on Galatians 6:10, the church father Jerome describes how John the evangelist, author of the gospel and the book of Revelation, preached at Ephesus into his nineties. Christian tradition holds that he died in about the year 100 CE.

|

|

St. Francis treating victims of leprosy, c. 1474.

|

At that age, John was so feeble that he had to be carried into the church at Ephesus on a stretcher. Then, when he could no longer preach a normal sermon, he would lean up on one elbow. The only thing he said was, “Little children, love one another.” People would then carry him back out of the church.

This continued for weeks, says Jerome. And every week John repeated his one-sentence sermon: “Little children, love one another.”

Weary of the repetition, the congregation finally asked, "Master, why do you always say this?"

"Because," John replied, "it is the Lord's command, and if this only is done, it is enough."

As the chaplain at Yale University, William Sloan Coffin (1924–2006) pushed back against intellectual idolatry. He observed how students at Yale “thought cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) was what it was all about, and Yale was encouraging them to think that." Coffin suggested a subversive alternative: "I felt very deeply that it’s amo ergo sum (I love, therefore I am).”

|

|

St. Francis preaching to the birds, c. 1260-1280.

|

This Latin phrase, amo ergo sum, which is actually the title of a 2002 book by the German cultural anthropologist Christina Kessler, can be translated slightly differently to make the point even more radical: "I am because I love." Or, as the farmer-poet Wendell Berry put it, I only live to the extent that I love.

In his book of poetry called Leavings (2012), Berry points the way for us in a short poem-prayer:

"I know that I have life

only insofar as I have love.I have no love

except it come from Thee.Help me, please, to carry

this candle against the wind."

Weekly Prayer

Saint Francis of Assisi (1182–1226)

The Peace Prayer of Saint Francis

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is error, truth;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

It is in self-forgetting that we find;

And it is in dying to ourselves that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.We do not know the author of this classic prayer, and it was not until the 1920s that it was even ascribed to Saint Francis. By one account the prayer was found in 1915 in Normandy, written on the back of a card of Saint Francis. But it certainly emulates his longing to be an instrument of peace, reconciliation and redemption in our fallen world.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) Wikipedia.org.