|

God Infinite, God Intimate

For Sunday June 7, 2009

Trinity Sunday 2009

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 6:1–8

Psalm 29

Romans 8:12–17

John 3:1–17

|

Egyptian god Sobek. |

As I walked through the Egyptian section of the British Museum a few summers ago, I marveled at the many ways that humanity has depicted God. The Egyptian god Sobek, for example, was pictured as a man with the head of a crocodile. Or consider the Hindu fire god Agni. He has two faces smeared with butter, seven tongues, gold teeth, seven arms, and three legs.

We could produce other images of the divine almost endlessly; such is the creativity of the human imagination. The philosopher John Hick once observed that if you collected all the notions of God that human religions have manufactured, they would fill a book the size of a telephone directory. Where did these images of God come from?

One theory of religion suggests that these "deities" are little more than our unconscious, psychological projections of our own insecurities. In this view, first propounded in a scientific way by Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), and later developed by Marx (1818–1883) and Freud (1856–1939), “religion is a dream, in which our own conceptions and emotions appear to us as separate existences, beings out of ourselves.” Theology, or talk about God, is thus reduced to anthropology, or talk about humanity. Prayer is talking to yourself.

|

Hindu god Agni. |

We shouldn't be too quick to dismiss this view. Feuerbach, Marx and Freud were wrong in what they denied (that God does not exist), but they were partly right in what they affirmed, that many of our images of God are human projections of our own making. Far too often, and Christians are not immune from this, we create God in our own, pathetic image. It's one thing for humans to be created in the image of God, but quite another for God to be created in the image of man. The prohibition of images in Judaism (Exodus 20:4) and Islam are partly an effort to curb this human tendency.

If I'm honest, it's disturbing to consider my pictures of God. There is God as Candy Man or Sugar Daddy who reinforces my self-aggrandizing narcissism. Sometimes God feels like the Absentee Landlord or Reclusive Neighbor. I know that He exists, but He feels hidden, silent, incommunicative, and far away. At least the Psalmists experienced and wrote about this image. God as Vending Machine, Concierge, or Short Order Cook is there to cater to my whims. To make my problems disappear there is God as Magician, and to engineer a parking space or fine tune some petty detail of my life there is God as Puppeteer. When I feel the weight of my faults and failures, God looms as a High School Principal, Probation Officer, or Divine Accountant. He snoops around in the dirty details of my life, exposes me, and I am found in arrears. In election season we get God as Partisan Politician to reinforce the worst sorts of patriotism (those that join throne and altar). This tribal deity inhabits both Republican and Democratic precincts. Over the 4th of July, God as National Mascot makes His appearance to reinforce our illusions of exceptionalism, that America is bigger, better, stronger and holier than any country on earth.

This deeply human impulse to create God in our own image is so strong, so misleading, and so dangerous that the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968) went so far as to describe the Gospel "revelation" (literally, something we could never know if God didn't tell us) as the Aufhebung (abolition, annulment, or invalidation) of all human religion. In Barth's view human religion and divine revelation are polar opposites. That’s a little extreme for my taste; Barth seems to throw out the baby with the bath water. But Barth was dealing with Hitler who claimed divine sanction, and his theological professors who had signed on to Hitler’s genocidal program, so his warning is well taken.

|

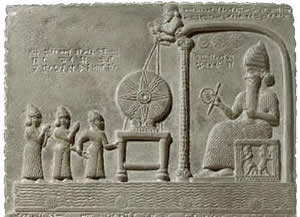

Babylonian sun god Shamash. |

Following Kierkegaard, Barth drew upon Scriptures like the two Old Testament readings for this week to emphasize the absolute transcendence of God. He is, as Barth put it, Wholly Other, and between the infinite God and finite humanity there is an Infinite Abyss. God is not to be caricatured or confused with human projections.

The "voice of the Lord" in Psalm 29 thunders over mighty waters. God's word is a powerful and majestic voice that splinters the cedars, twists the oaks, and rips the bark off a tree. The psalmist compares this voice to the flash of lightning. Similarly, Isaiah envisions God "high and lifted up." Celestial creatures surround His throne in worship, covering their eyes at the very sight. "At the sound of their voice," writes Isaiah, "the doorposts and thresholds shook and the temple was filled with smoke." The transcendence of God means that in our sin and finitude we need to be very careful about our images of the Infinite.

The two readings from the New Testament this week deepen our understanding. God is not only transcendent. Yes, He is infinite, mysterious, and beyond human knowing. But we should never imply that He is unknowable. Rather, He is immanent, not only high and lifted up but near and dear to every person. The first words of the Lord's Prayer capture this perfectly, “Our Father, who art in heaven.” If these words from Luke 11:1–13 are to be trusted, and Christians believe they should be, Jesus tells us that if you want to know what God is like, He is like a loving Father.

Paul says the same thing when he writes to the Romans. We should not relate to God as a slave who fears a master, but rather as a child in a filial relationship with a protective parent: "Abba, Father" (Romans 8:15, Galatians 4:6). As many people have observed, Abba is the Aramaic word for something like "Papa." The word is used only three times in the New Testament, and conveys a shocking sense of intimacy (not informality). It's a word that little children first learning to speak use for their father, and that Jesus himself used to speak to God in Mark 14:36.

During the four years that my family lived in Moscow (1991–1995), we took the overnight train to St. Petersburg a number of times. There, we visited the Hermitage Museum which houses Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son (1666). The painting is enormous (262 X 205 cm), and full of deep, dark reds and browns. In it, the bent over father embraces his kneeling son — with compassion, with tenderness, and without any questions about his many failings.

|

Rembrandt, The Return of the Prodigal Son. |

What is God like? Jesus says that He is like an earthly Father who does anything to bequeath all that is best to his children. He is like a loving Father who embraces us and welcomes us home. He is strong, affectionate, protective, impeccably safe, and unconditionally loving. In his work of redemption Jesus reconciles us to this loving God; in His work of revelation He shows us what this God is like: “He who has seen me has seen the Father" (John 14:9).

I’ve always appreciated the Eastern Orthodox emphasis on “apophatic” theology, the notion that the transcendent God is beyond human definition and comprehension, yet at the same time truly immanent. In his book Encountering the Mystery; Understanding Orthodox Christianity Today (2008), Bartholomew I, His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch, summarizes this perfectly: “God as unknowable and yet as profoundly known; God as invisible and yet as personally accessible; God as distant and yet as intensely present. The infinite God thus becomes truly intimate in relating to the world” (186).

For further reflection

* When have you experienced God as especially remote? Near? Can you discern why?

* How do we hold together God "so far" and "so near" without losing either?

* What are the consequences of stressing only the transcendence or immanence of God?

* For further study, see Donald McCullough, The Trivialization of God; The Dangerous Illusion of a Manageable Deity (1995), and Henri Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal.

Image credits: (1) The British Museum; (2) Vahini Art Gallery; (3) www.geocities.com/Athens/Parthenon/; and (4) RembrandtPainting.net.