He Too Was Distressed

For Sunday December 26, 2004

First Sunday After Christmas

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 63:7–9

Psalm 148

Hebrews 2:10–18

Matthew 2:13–23

|

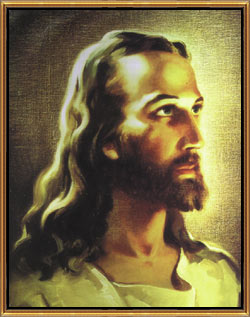

Head of Christ by Warner Sallman (1940) |

Lining the hallway in our house there hang a number of baby pictures of our three children. Is that what they really looked like twenty years ago? Having just celebrated the birth of baby Jesus, it is fascinating to ask a question that, admittedly, we cannot answer: what did Jesus look like? If you are a white, American, Protestant, your images of Jesus were probably formed by one of the most reproduced pictures ever, The Head of Christ (1940) by Warner Sallman. One scholar suggests that Sallman's saccharine image of Jesus with blondish hair, blue eyes and fair skin has been reproduced over 500 million times. You'll find this reproduction not only here in America but, improbably, even in churches around the world.

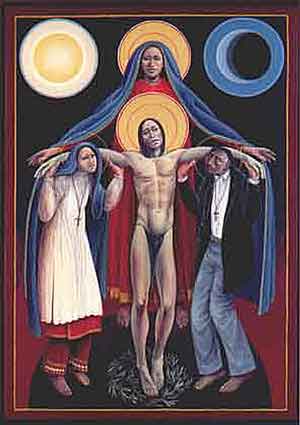

But no one has an interpretive monopoly on images of Jesus, not even Sallman. In their respective books, Stephen Prothero (American Jesus; How the Son of God Became a National Icon, 2003) and Richard Wightman Fox (Jesus in America; Personal Savior, Cultural Hero, National Obsession, 2004) document how people have created Jesus in their own image according to their own time, place, and culture, and how our notions of him have become extraordinarily elastic. There is the Jesus of European colonizers and the Jesus of cultural kitsch, the Jesus of German intellectuals and of Guatemalan Indians, the Jesus of stage, theater, song and film. Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) excoriated a "slave-holding, women-whipping" Christendom. Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) took scissors to all that offended his eighteenth-century concept of reason in the Gospels, and ended up with a Jesus who was little more than a sage. George Bush claimed Jesus as his favorite political philosopher. Philip Yancey wrote a book called The Jesus I Never Knew (1996), while in the very first chapter of his new book A Generous Orthodoxy (2004) Brian McLaren pays tribute to "The Seven Jesuses I Have Known." In one of the more famous metaphors ever suggested in theology, in his Quest for the Historical Jesus (1906), Albert Schweitzer compared the 19th-century liberal search for the "real" Jesus, scrubbed clean of centuries of historical accretions, to people gazing down a well and seeing only their own reflections.

|

Black Joseph with the Young Jesus by Wiktor Szostalo |

These thoroughly malleable, complementary, and sometimes competing images of Jesus are fascinating at a cultural or sociological level. Practically, they inform how people live their Christian lives. But most importantly, and at a deeper level still, on a theological level they reveal just what it is that we think about God, for in the words of Hebrews 1:3, Christians believe that Jesus is "the exact representation of God's being" (NIV). As go our beliefs and images about Jesus, so go our notions about God. In the infancy narratives about Jesus from the Gospel of Matthew for this week (Matthew 2:13–23), we learn some interesting things about Jesus that connect with a 700-year old image of Yahweh from the prophet Isaiah.

We know from Luke that Jesus was born in a "manger" because "there was no room in the inn." This quaint language has so embedded itself in our psyches that it obscures some uncomfortable facts—the one whom Christians worship as the Son of God was born in a filthy stall among farm animals because neither the business owner nor his paying customers would give up their bed to a pregnant teenager who was in labor. Such is the picture from earth, among the common affairs of ordinary people.

|

Native American Christ |

There is another birth narrative in the New Testament that I have never heard read at Christmas. This birth narrative takes place in heaven, bursting with apocalyptic imagery from a cosmic perspective. From the book of Revelation we read about a woman crying out in labor pains as she gives birth to "a son, a male child, who will rule all the nations with an iron scepter." An enormous red dragon stands in front of her spread legs, "so that he might devour the child the moment it was born" (Revelation 12:1–13:1). On earth, the baby Jesus was ignored as an inconvenience by calloused, self-interested people; in heaven, an enraged dragon, Satan, sought to destroy him.

Matthew's telling of the birth and infancy of Jesus centers around five dreams, four of which were by his father Joseph and one by the Gentile Magi or Wise Men. He adds tantalizing details about the infancy of Jesus. In Joseph's second dream God warned him that King Herod intended to kill Jesus, and instructed the young family to flee to Egypt for safety. This is the same Herod the Magi were warned to avoid in their own (the fifth) dream. The ironies are breathtaking. The infant Son of God fled as an alien, immigrant, displaced refugee to a foreign country, Egypt, Israel's sworn and symbolic enemy that oppressed the Hebrews for 430 years (Exodus 12:40). The same place where Pharaoh had unleashed an infanticide against the Israelite children (Exodus 1:6–22) became a place of refuge for Jesus. In his third dream a few years later, God instructed Joseph that Herod had died, so the peripatetic family returned to Judea in Israel. But after learning that Herod's son Archelaus reigned in place of his father Herod, Joseph feared for their lives, and in a fourth dream God instructed him to move his family yet again, this time to Nazareth of Galilee. I have wondered what connection there might have been between the earthly Herod who tried to murder Jesus, and the enraged, cosmic dragon of Revelation who stood ready to devour the baby at birth. Finally, after a short life in which he was spurned as the friend of gluttons and sinful people, those same political powers did succeed in killing Jesus.

|

Russian Orthodox Christ |

And what a death. After an ignomious birth that rocked the cosmic powers, early years wandering in enemy Egypt, and then a controversial and tumultuous life, Jesus was crucified between two criminals "outside the city gate" (Hebrews 13:12), that is, on the outskirts of Jerusalem at the municipal garbage dump, a place of disgust, shame and reproach. Such was "the disgrace he bore," adds the writer (Hebrews 13:13). In the epistle for this week (Hebrews 2:10–18), this same writer reminds us that in taking on our own flesh and blood, Jesus "shared in our humanity." No, we are not angels who need help, he writes, far from it. The "textual" image of Jesus says that "he was made like us in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest." Like us, he suffered, he was tempted, he hurt, he fled and feared for his life, he was forced to move because of circumstances beyond his control, and people tried to destroy him.

All of which is to say that these textual images of Jesus reveal to us a God of infinite empathy, tender compassion, kindness and goodness. He is a God eager to help and able to save, a God who in Jesus experienced all the extremities of human dereliction and deprivation. He is a God "down and dirty" with us. Tracking backward 700 years to the Old Testament text for this week, the Hebrew prophet Isaiah summarized the God of Jesus in this way: "In all their distress, He too was distressed" (Isaiah 63:9). That is an image of God in Christ a long, long way from Sallman's rosy-cheeked mystic who does little more than stare vacantly into space, and I dare say an image far closer to reality.